Moments of Silence

The studio where John MacDonald paints sits partway up a hill on the edge of the woods in South Williamstown, Massachusetts. His house, which lies close to the road on the other side of a footbridge and a stream, is beige and nondescript. The studio, however, resembles a storybook  cottage, shingled and snuggled into the hillside, with a sharply pitched roof and a set of steep steps leading to the door. It looks like the setting of a story about a hermit or an eccentric poet, something one might glimpse and then wonder about while driving up Route 43 into town.

cottage, shingled and snuggled into the hillside, with a sharply pitched roof and a set of steep steps leading to the door. It looks like the setting of a story about a hermit or an eccentric poet, something one might glimpse and then wonder about while driving up Route 43 into town.

Quaint cottages like MacDonald’s studio are notably absent from the artist’s own paintings, realistic oil landscapes that recall the nineteenth or early twentieth century more than they do the twenty-first. His works don’t contain many barns, grazing cows, or rough-hewn fences, either. Though MacDonald’s landscapes are quintessential Berkshire scenes, they are stripped of human influence, the buildings and other marks of civilization that exist in real life edited out as he sees fit. Instead, his paintings are populated with rocks and streams and trees and hills and even a few wildflowers, all cast in intricately rendered light and shadow. They are depictions of nature unadorned.

MacDonald is not interested in telling a story in his paintings. He searches for something more elemental that exists independent of human history and culture. Buildings situate a landscape in time; MacDonald strives for timelessness. “I’m less interested in it looking like a finely detailed scene than I am suggesting that sense of emptiness and silence that’s underneath that scene,” MacDonald says. “I’m most interested in grappling with this challenge of how do you portray silence, how do your portray absence?”

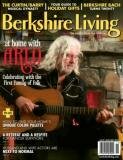

MacDonald, who at fifty-three years old is wiry and boyish, with big, round blue eyes and a shock of blond hair, doesn’t look or act like someone who spends much time contemplating nature’s immutable qualities. He speaks quickly and animatedly, zooming from one subject to another, as if in motion even when he’s scarcely moving. He is amiable and friendly, with a slight Midwestern accent from his boyhood in Lafayette, Indiana. Perhaps in keeping with his demeanor, his paintings tend to have an inviting atmosphere, conveying tranquility without appearing lonely or desolate.

“There’s a sense of intimacy in his painting, which really draws your eye,” says Jocelyn Grayson, art sales and exhibitions director at the Southern Vermont Arts Center in Manchester, which has exhibited MacDonald’s work in solo and group shows. Despite the calm that pervades his art, she says, “there is something magnetic about the work that people gravitate toward and find memorable.”

That magnetism, however, is subtle. “With some artists you feel that they’re leading you everywhere in the painting,” Grayson explains. “You feel their sense of composition, there’s an obvious way in which your eye is directed to navigate the painting. You don’t get that sense with John’s work. What draws you in is more a sense of your own discovery.”

Indeed, MacDonald’s paintings tend to conjure a sense of having stumbled upon some lovely, hidden-away scene or even a familiar vista seen from a new angle. MacDonald spends a lot of time walking in the woods and hills around his house, mostly for meditation, but also for inspiration. His studio is filled with souvenirs from his wanderings: rocks whose surface he’s drawn to, cow bones, a large piece of cobweb-covered driftwood from when he lived in Nova Scotia. MacDonald collected many of these items because he was struck by their interesting textures, and he talks about “seeing in 3-D”—noticing not designs or patterns, as his wife, Deborah, a devoted quilter, does, but perspective and depth. He’s a formalist. His interest in painting a subject almost always has to do with shape or color, rather than a narrative behind it: the way a river cuts through a meadow or the way light hits a field to create a golden triangle pushed up against a soft mash of shadows.

Indeed, MacDonald’s paintings tend to conjure a sense of having stumbled upon some lovely, hidden-away scene or even a familiar vista seen from a new angle. MacDonald spends a lot of time walking in the woods and hills around his house, mostly for meditation, but also for inspiration. His studio is filled with souvenirs from his wanderings: rocks whose surface he’s drawn to, cow bones, a large piece of cobweb-covered driftwood from when he lived in Nova Scotia. MacDonald collected many of these items because he was struck by their interesting textures, and he talks about “seeing in 3-D”—noticing not designs or patterns, as his wife, Deborah, a devoted quilter, does, but perspective and depth. He’s a formalist. His interest in painting a subject almost always has to do with shape or color, rather than a narrative behind it: the way a river cuts through a meadow or the way light hits a field to create a golden triangle pushed up against a soft mash of shadows.

Admirers praise MacDonald’s composition, use of light and color, and ability to create a sense of depth that draws the eye effortlessly into the painting, back toward the mountains and the horizon. He’s drawn to atypical vantage points—the view of a stream and snow-covered banks not as they would appear from a well-trafficked road, but seen, in one painting Grayson exhibited this summer at the Southern Vermont Arts Center, as though the viewer were hovering several feet above the surface of the water. Looking at it, one isn’t aware of hovering; the dark river winds into the background, one snowy bank cast in shadow, the other illuminated and helping to draw the eye toward some distant hills bathed in a rosy pink. Like many of MacDonald’s winter tableaux, this one is unexpectedly warm and inviting. Tufts of grass catch the light, and the sky is shrouded in a soft  haze that’s perhaps more typical of a Berkshire summer. It’s cold, and yet it makes you want to be there.

haze that’s perhaps more typical of a Berkshire summer. It’s cold, and yet it makes you want to be there.

For years, MacDonald was right there, painting en plein air in the manner of the nineteenth and early twentieth-century landscape painters he so admires, such as Willard Metcalf and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. He worked at temperatures down to about 10 degrees; any colder and his fingers froze up. As his interest has shifted from presenting sweeping panoramas on small canvases to portraying more intimate scenes on larger canvases, he has moved inside, taking photographs when a view catches his eye and then retreating to his studio. The photos allow him to freeze time and explore patterns, shapes, and color relationships rather than feeling compelled to throw paint on the canvas to capture a rapidly shifting cloud pattern or a changing light. He still extols the value of plein-air painting, but contends that years spent painting outdoors have trained his eyes to fill in whatever a snapshot doesn’t capture to get to the essence of the setting.

Inspired by the European and American impressionists and Chinese landscape painters of the twelfth- through seventeenth-centuries, whom he considers masters of simplicity, MacDonald situates his style as being “somewhere between 1860 and 1930,” he says. “There’s so much there—lessons I can derive from their work for three lifetimes, easily.”

In the past decade, MacDonald’s fine art has taken up a growing portion of his time and provided a  growing portion of his income, but for nearly thirty years he has made his living as a commercial illustrator for magazines and advertising campaigns. Before that, during college at Washington University in St. Louis, he spent summers working as a railroad gang laborer in Indiana, as a logger in Montana, and on an oil pipeline barge in the Gulf of Mexico. He met his wife, Deborah, who was then a speech-pathology student, while completing his master’s at Purdue University. After that, the two moved wherever she got a job; they spent two years in Laconia, New Hampshire, another two in Nova Scotia (where MacDonald learned to paint seascapes), two more in Bennington, Vermont, and six in Cherry Valley, New York, about sixty miles west of Albany, before settling in Williamstown fifteen years ago with their two sons, who are now grown. With the advent of the Internet, MacDonald was able to work from anywhere, creating advertisements for Citibank, covers for U.S. News & World Report and the German newsmagazine Der Spiegel, as well as other editorial work for Barron’s, the Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post.

growing portion of his income, but for nearly thirty years he has made his living as a commercial illustrator for magazines and advertising campaigns. Before that, during college at Washington University in St. Louis, he spent summers working as a railroad gang laborer in Indiana, as a logger in Montana, and on an oil pipeline barge in the Gulf of Mexico. He met his wife, Deborah, who was then a speech-pathology student, while completing his master’s at Purdue University. After that, the two moved wherever she got a job; they spent two years in Laconia, New Hampshire, another two in Nova Scotia (where MacDonald learned to paint seascapes), two more in Bennington, Vermont, and six in Cherry Valley, New York, about sixty miles west of Albany, before settling in Williamstown fifteen years ago with their two sons, who are now grown. With the advent of the Internet, MacDonald was able to work from anywhere, creating advertisements for Citibank, covers for U.S. News & World Report and the German newsmagazine Der Spiegel, as well as other editorial work for Barron’s, the Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post.

MacDonald’s illustrations, which resemble nineteenth-century woodblock prints, differ strikingly from the lush, soft wash of his oil paintings. Their basic elements—a strong sense of design and of light and dark, spaces structured realistically—carry over into both genres. Pamela Budz, design director at Barron’s and MacDonald’s editor since the mid-1990s, notes the richness of MacDonald’s color palette and his skill at depicting light at different times of day—a legacy, perhaps, of his years observing changing light patterns while painting outdoors.

For his commercial work, MacDonald uses a brush to apply black ink to a white, clay-based  scratchboard, then scrapes a design into the ink. In the early 1990s, as he began getting more assignments in color, MacDonald took to scanning his designs into Photoshop and filling in the colors digitally. Doing so allowed him to make changes without starting over with a fresh scratchboard, a boon with deadlines sometimes as tight as just eight or ten hours.

scratchboard, then scrapes a design into the ink. In the early 1990s, as he began getting more assignments in color, MacDonald took to scanning his designs into Photoshop and filling in the colors digitally. Doing so allowed him to make changes without starting over with a fresh scratchboard, a boon with deadlines sometimes as tight as just eight or ten hours.

Local professional models being scarce, MacDonald mostly works from photos of himself and family in his illustrations, though friends and neighbors make appearances, too. (Rob White, director of alumni communications at Williams College, posed as Pinocchio for a post-Enron Barron’s cover article about the trustworthiness of corporate CEOs). MacDonald’s two sons frequently served as models when they were growing up, but since they’ve left the house, MacDonald—who just so happens to have a particularly malleable and expressive face—has been his own most reliable model.

In his fine art work, MacDonald wills himself to paint slowly and deliberately, but commercial work requires that he deliver what art directors want, and on deadline.

“When I’m creating a [commercial] piece, I’m always creating that piece out of a place of strength, what I know how to do and do…well,” MacDonald says. “Whereas I think it’s important for fine artists to always be on their edge, to really be creating out of their weaknesses. You need to put yourself in a place where you’re not sure where it’s going, because it’s in that place of not knowing where a lot of life can come into a piece.”

MacDonald developed his commercial style partly as a deliberate contrast to his landscape painting, a subtle reminder that illustration is something he does for money, painting he does for, as he puts it, “my soul.” In the past decade, MacDonald bridged that gap somewhat with fine-art works he dubs “digital woodcuts.” The technique is similar to that of his commercial illustration in that he renders the outlines of the image by hand before scanning it and adding layers of color on the computer. Depending on how finely wrought, the prints can closely resemble either traditional Japanese woodcuts or detailed etchings. They also often contain the buildings that MacDonald tends to eschew in his painting; structures lend themselves well to the blocky, graphic style, though over time he has shifted to softer, more realistic images.

Though MacDonald’s styles are strikingly different, they both sell well. Of the forty regional artists represented at the Harrison Gallery in Williamstown, MacDonald is one of the most popular, seeming to appeal to the full range of buyers: locals, Williams College alumni and relatives of current students, second-home owners, and “art tourists.”

Though MacDonald’s styles are strikingly different, they both sell well. Of the forty regional artists represented at the Harrison Gallery in Williamstown, MacDonald is one of the most popular, seeming to appeal to the full range of buyers: locals, Williams College alumni and relatives of current students, second-home owners, and “art tourists.”

“He is loved and admired and collected uniformly in all of those groups,” says gallery director Jo Ellen Harrison. “They love that he really captures the beauty of the Berkshires without being illustrative or trite.”

For many, MacDonald’s traditionalism is precisely his appeal. Viewers see modern and contemporary works at MASS MoCA and the Williams College Museum of Art, Harrison says, “and then they see John MacDonald—it’s like a sigh of relief: ‘This is beautiful, I connect with it ... and it’s okay that it’s a naturalist painting, because it’s so well executed, so developed in its aesthetic.’”

MacDonald insists he isn’t thinking about the viewer as he paints; inevitably, one brings individual experiences, opinions, and reactions to a painting. “I’m not really trying to convey this to a viewer as much as I am just trying to capture it for myself,” the artist says. Hence his resistance to narrative elements, his emphasis on form, and his restrained use of detail.

“He’s finding the common human thread of our relationship to the landscape,” Harrison says. “That’s not anticipating what will be liked or what will sell. He’s basically meditating or getting to an essence that we all respond to.”

Indeed, with his talk about immersing himself in the countryside and trying to conjure a sense of calm and presence in nature, MacDonald sounds quite Zen. He is, however, as conflicted and ambivalent and worried about his work as any serious artist; that’s the nature of what he calls “painting on your edge.” The line between realism—straight out visual description of an environment—and suggestion intrigues him. Up close, his canvases are quite rough, even crude in spots. As a viewer steps away, there’s a point at which “everything snaps” and the blobs of paint become a scene.

“I love that tension between the realism and yet the fact that it’s just paint on canvas,” MacDonald  says. “At what point is it just a brushstroke, and at what point is it a convincing sense of light across a rock or a field?”

says. “At what point is it just a brushstroke, and at what point is it a convincing sense of light across a rock or a field?”

The artist worries about relying on his strengths—his facility with light and dark, his ability to render convincingly—to call attention away from fundamental problems elsewhere in the painting. Strengths can also be weaknesses, and, to hear him describe it, his painting involves a process of constant self-monitoring to balance his love of beauty with a sense of good composition.

“There is a beauty in light and there is a beauty in color,” MacDonald says. “In our cynical day and age, you can’t celebrate that too openly or it comes off as looking very sentimental and kitsch.” Moreover, he is increasingly convinced that his paintings are about silence—too much richness undermines that aura.

Self-criticism is valuable to any artist, but MacDonald may be more willing to discuss it than most. “It’s very easy to slip from a simple statement of fact, ‘Boy, this green isn’t working,’ to ‘Boy, I never do greens well,’ to ‘Boy, I’m a lousy landscape painter,’ to ‘Boy, I should’ve gotten an MBA,’” MacDonald says. “We get into this self-critical mode where we trash ourselves very quickly.”

A few years ago, MacDonald picked up a book by the writer and psychotherapist Eric Maisel that promised a method of escaping such negative thought processes. MacDonald credits Maisel, who founded a hybrid therapy movement called creativity coaching, with helping him be more productive, focused, and willing to take chances. Inspired, MacDonald decided to become a certified creativity coach himself. Over two years, in the midst of his commercial illustration and fine-art work, he  completed the certificate through a combination of online courses, supervised coaching, and other coursework. The practice remains, at most, a side activity—he counsels about three to four clients a year, most of them artists, by phone or e-mail, sometimes with those as far away as South Africa or New Zealand. Generally, they work for a few months on issues of anxiety and fear. The goal is self-awareness and, as MacDonald quips, “not playing games with yourself.”

completed the certificate through a combination of online courses, supervised coaching, and other coursework. The practice remains, at most, a side activity—he counsels about three to four clients a year, most of them artists, by phone or e-mail, sometimes with those as far away as South Africa or New Zealand. Generally, they work for a few months on issues of anxiety and fear. The goal is self-awareness and, as MacDonald quips, “not playing games with yourself.”

MacDonald remains entranced by light and beauty, but says his appreciation for subtlety is growing. He prefers the stark light and the simple color palette of winter; when it comes to fall foliage, he likes to paint the leaves post-peak, as their colors are fading. He keeps telling himself he’ll venture to other parts of the region for different scenery, but he keeps discovering new surroundings on walks within a mile or two of his house.

“There’s an endless amount of material,” MacDonald says. “The palette’s different every day. I don’t need to go away to come back and see things. If I just open my eyes...” he trails off.

“The challenge is just keeping your eyes open and seeing what’s out there.” [OCTOBER 2010]

Williamstown, Mass., native Kaitlin Bell Barnett is a freelance writer living in Brooklyn, N.Y.

THE GOODS

John MacDonald

1021 Hancock Rd./Route 43

Williamstown, Mass.

Creativity Coaching by

John MacDonald

Williamstown Landscapes

by John MacDonald

Oct 2-31

Reception Oct 2 at 5-7

The Harrison Gallery

Williamstown, Mass.

Delicious

Delicious Digg

Digg StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Propeller

Propeller Reddit

Reddit Magnoliacom

Magnoliacom Newsvine

Newsvine Technorati

Technorati