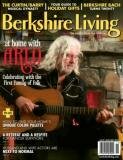

MUSIC: John Williams, Pops Star

Although John Williams is the quintessential Hollywood composer, widely considered the most successful of all time, his roots are in New England and his heart is in the Berkshires. As the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s official artist-in-residence at Tanglewood in Lenox, Massachusetts, he spends a month at the orchestra’s summer home, where he conducts the Boston Pops in Film Night, an event he created in 1997 and has performed annually in various formats since 2000; it’s now also staged in Boston and at the Hollywood Bowl. Williams, 78, also steals away to Lenox at other times of the year, staying at the same Blantyre cottage—he has his Steinway grand shipped in so he can pursue his daily composing regimen.

Williams’s avuncular appearance and modest demeanor belie his iconic status; when he takes the stage at Tanglewood, he gets a hero’s welcome comparable only to the full-throated roar that greets James Taylor. On Saturday, August 14, the twelfth Film Night will mark the thirtieth anniversary of Williams’s first appearance at Tanglewood, back in 1980, when he succeeded Arthur Fiedler as chief conductor of the Boston Pops, a post he held for thirteen years. He’ll conduct a portion of Tanglewood on Parade on August 3 as well.

As Williams explains during a phone interview from his Los Angeles office (which is near Steven Spielberg’s), New England holds fond memories. “My parents were New England people,” he says, though he grew up in New York on Long Island before relocating to California, where he attended UCLA. His father, jazz percussionist Johnny Williams, was a native of Bangor, Maine, and Williams remembers the family homestead “from my four or five-year-old child’s eye.” He plans a visit there this month. His mother, Esther, a Boston native, took Williams to Lake Cochituate in the Framingham-Natick area every summer until he was twelve. “We had a house on a lake, where I learned to swim, fish, and boat,” he recollects. “As a child, I was very much in love with the whole look of New England. It’s the music that brings me there now, with these conscious and unconscious connections throughout my life. It’s a wonderful combination of a vibrant present and a long string of memory, so it’s very resonant for me.”

Williams, who hopes for a minute or two of usable music from each day of his composing routine, plans to spend some time this month working with Spielberg on the finishing touches for The Adventures of Tintin: Secret of the Unicorn, due for release next year. Williams has composed the music for all but one of Spielberg’s twenty-five big-screen films (Quincy Jones scored The Color Purple). He is keen on the notion of encouraging Spielberg, who “loves the Berkshires as much as I do” but spends summers in the Hamptons of eastern Long Island, to move here instead.

“I’ve often said that when Johnny sees one of my movies, he does a musical rewrite and makes the picture so much better than I ever could have imagined,” Spielberg says in an e-mail message. “His music has deepened the souls of characters and lends an almost ineffable meaning to the stories we’re telling.”

Characterizing his lengthy connection with Spielberg in equally complimentary terms, Williams describes the director and producer as “a loyal person, very easy to be with, a warm temperament uncluttered by vanity. He’s a very generous person, not  nervous in collaborations, as a lot of people can be. He has an easy sense of confidence, and doesn’t worry about the outcome—a man who’s very comfortable in his own skin. It’s [been] like a wonderful marriage without any arguments for the past thirty-seven years.”

nervous in collaborations, as a lot of people can be. He has an easy sense of confidence, and doesn’t worry about the outcome—a man who’s very comfortable in his own skin. It’s [been] like a wonderful marriage without any arguments for the past thirty-seven years.”

Williams planned this month’s Film Night as a tribute to Spielberg in honor of their work together; Robert Osborne, a host on cable’s Turner Classic Movies, will narrate the program.

Williams acknowledges “very subtle differences” when he works in Lenox rather than in Hollywood. “In the Berkshires, one is out of the urban noise, bustle, and tempo of what’s in every city, obviously in Los Angeles, though my studio here is very isolated and quiet,” he explains. “The difference is in sound, light, weather, trees, the beautiful sacred trees that we don’t have here [in L.A.], and being able to be quiet in the company of these dignified, majestic plants.”

He welcomes the slower pace and fewer distractions of his Berkshire retreat. “The days are elongated by the beauty and quietude,” he says. “It’s a great place to work and write, as its long and rich literary history indicates.” Among his many scores written here are those for Schindler’s List and the first two Harry Potter films, and the cello concerto written for Yo-Yo Ma. His composing plans this month include completion of a quartet for violin, clarinet, and two cellos to be premiered at the La Jolla (Calif.) Music Festival.

From his office window, Boston Symphony managing director Mark Volpe often sees John Williams walking the Tanglewood grounds, deep in contemplation, a sight he finds inspiring. For Volpe, Williams is a “legendary, dominant figure, a composer of this period whose music will live far beyond our lifetimes. That’s a given.”

Williams ranks with the “pantheon of figures who embody the spirit and ethos of Tanglewood—Koussevitzky, Copland, Bernstein, Ozawa—though he would probably be embarrassed to hear me say it,” Volpe continues. “When you meet the guy, he’s so modest and unassuming. He’s not just a musical genius, but he’s also so well-read and articulate. When I need wisdom or help with something, he’s one of the guys I would just sit with and talk. He’s got great judgment and enough distance that he can be objective.”

embarrassed to hear me say it,” Volpe continues. “When you meet the guy, he’s so modest and unassuming. He’s not just a musical genius, but he’s also so well-read and articulate. When I need wisdom or help with something, he’s one of the guys I would just sit with and talk. He’s got great judgment and enough distance that he can be objective.”

The modesty comes through when Williams is asked to cite several lesser-known film scores (among his more than one hundred) that he feels represent some of his best work. “I might have done better here and there,” he says, adding reluctantly that “there are passages in Close Encounters that I enjoy. The Jane Eyre production in England [released in 1971, starring George C. Scott and Susannah York] has a few cues I still find interesting enough. I have very active and different feelings about all my work.”

Composing for film in Lenox is easier now than it was thirty years ago; Williams works from DVDs as well as script notes. “These have been thirty fleetingly passing years, each one beautiful,” he reminisces. “It’s a wonderful tradition every summer since there isn’t any other place I’d rather be.”

Nearly always, Williams explains, he composes film “cues” after seeing each scene, “writing the music in close relationship to all the action so it fits the timing.” The only exceptions were the Hedwig theme from Harry Potter and Oliver Stone’s JFK—in both cases, the score was pre-recorded. Normally, Williams screens the rough cut of the film and then works backward from the final scene: “It’s always better to see the whole film from beginning to end to get a sense of the arc.” By composing the themes for the conclusion first, “they can be presented in earlier scenes, and then it can be a very satisfying sense of inevitability.”

Williams, who has won five Oscars for his scores and has been nominated forty-five times (second only to Walt Disney), learned from the master Hollywood composers of the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s—he lists as key influences Alfred Newman, Franz Waxman, Victor Young, Dimitri Tiomkin, and especially Bernard “Benny” Herrmann, who teamed with Alfred Hitchcock (Psycho, Vertigo and North by Northwest, among others). Ironically, Williams scored Hitchcock’s final film, Family Plot, in 1976. “Benny was enormously encouraging to me; he was perhaps a mentor,” says Williams. “His music has a particularly idiosyncratic, highly personal stamp, insistent and very powerful dramatically.”

Pleased that film music is an art form now taken more seriously than when he entered the business nearly sixty years ago, Williams notes that there are now film departments at universities nationwide. “It’s a very different attitude now,” he adds, “though there’s still much condescension, a lot of it perhaps deserved.”

Pleased that film music is an art form now taken more seriously than when he entered the business nearly sixty years ago, Williams notes that there are now film departments at universities nationwide. “It’s a very different attitude now,” he adds, “though there’s still much condescension, a lot of it perhaps deserved.”

As for the future of orchestral music, Williams foresees more focus on audio-visual multimedia experiences, though the “precious repertoire is one of our great inheritances; the canon of Western musical literature is so important to our lives, and that’s the preservation aspect. The orchestra is one of the great inventions of the Western mind, a fantastic delivery system of music that needs to be cherished and nurtured. But as a very exciting adjunct to this tradition, we’ll still play Beethoven in the right environment but also develop experiments in new works.”

With many major and regional orchestras facing financial challenges as audiences gradually age and dwindle, Williams anticipates greater reliance on “a creative synthesis drawn from both high art and popular culture” that would include “atmospherics and lights.”

His successor at the Boston Pops, Keith Lockhart, now in his fifteenth season, describes Williams as “probably the most famous living composer in the world. Without him, eighty percent of the audience wouldn’t hear the symphony orchestra. The gift he has given us is the connection to the most vibrant and interesting film music ever composed. He’s a wise, gentle spirit, a calm, Zen-like presence. In our field, things that are too popular are always suspect. You certainly need somebody who takes film music out to be celebrated and he has done that.”

presence. In our field, things that are too popular are always suspect. You certainly need somebody who takes film music out to be celebrated and he has done that.”

Caroline “Kim” Taylor, longtime Boston Symphony director of public relations and now an overseer of the orchestra, met Williams in 1980. It was, she says, “my first year at the BSO and his. He always says we were in the ‘same class.’” And it was Williams who first introduced her to James Taylor backstage at a Pops performance in 1993. When James and Kim were married in 2001 in the Lindsey Chapel of Boston’s historic Emmanuel Episcopal Church, Williams walked her down the aisle. “My father had died six months before I had met James, so it was wonderful to have John there in that special role,” she says.

“John is one of the rarest of individuals—his humanity matches his genius,” Kim Taylor continues. “I thought I fully appreciated his talent, but recently I’ve gained a new perspective. As the mother of twin nine-year-old boys, I’ve been re-living many of John’s masterpieces: E.T., Superman, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and first and foremost, Star Wars. One realizes how John’s scores add such depth, majesty, mystery, and pathos to each one. There is no question in my mind that his music will outlive all of us. I think he may be even more appreciated in the future when the false distinction between ‘high art’ and film will have disappeared and John can assume his rightful place as one of the truly great composers of all time.”

James Taylor also offers high praise: “New orchestral music finds its healthiest milieu today in film, and John Williams is the king of film scorers.... It is the cultural impact of his scores, the depth of the emotional response of his audience to his music that will, I am positive, assure his place in music’s pantheon a hundred years from now. The opportunity to work with him personally has been one of my own most cherished accomplishments in this lucky life. He is completely secure and able  in the most extremely demanding and complex endeavor; he radiates a quiet authority and possesses such an easy ability to communicate at all levels of artistic collaboration that it is a joy and a wonder to work with him. He is, quite simply, a master.”

in the most extremely demanding and complex endeavor; he radiates a quiet authority and possesses such an easy ability to communicate at all levels of artistic collaboration that it is a joy and a wonder to work with him. He is, quite simply, a master.”

The Taylors’ admiration is shared by those who have had their own close encounters with Williams. That he views the Berkshires as his second home and Tanglewood as his spiritual center of gravity is a gift treasured by the more than fifteen thousand listeners who keenly anticipate each of his annual podium appearances here. [AUGUST 2010]

Clarence Fanto, an independent journalist and contributing editor to Berkshire Living, reviews music for www.berkshireliving.com. A longtime Lenox, Mass., resident, he has attended and reviewed every John Williams performance at Tanglewood.

THE GOODS

Tanglewood on Parade

Aug 3 at 8:30

Boston Symphony, Boston Pops,

and the Tanglewood Music Center

Orchestra Conducted by John Williams,

Keith Lockhart, Stefan Asbury

Film Night

Aug 14 at 8:30

John Williams conducts a musical tribute

to Steven Spielberg, narrated by Robert Osborne

Tanglewood

Route 183

Lenox, Mass.

Delicious

Delicious Digg

Digg StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Propeller

Propeller Reddit

Reddit Magnoliacom

Magnoliacom Newsvine

Newsvine Technorati

Technorati